| |

| |

PLACES WORTH SLOWING DOWN FOR

Visiting Overlooked Towns and Places |

|

| |

Story and photos by Lee Juillerat |

|

Ever wonder about some of the places you drive past? Who lives there? Where does that side road lead? How did the name come about? It’s not unusual to buzz past some tiny community or not take the time to explore a side road.

Following are three vignettes of places worth knowing. One is off the highway between Lakeview, Oregon, and Denio, Nevada. A second was part of a former logging railroad, while the third is in remote Nevada near the Black Rock Desert.

The three communities are among those featured in Far Corners 2: Seldom Seen Places in the Land of the Lakes, the 2021 journal published by the Shaw Historical Library in Klamath Falls, Oregon. This selected trio is just part of the 27 entries by a variety of authors. The three stories are abbreviated versions by Lee Juillerat.

Kinney Camp

Kinney Camp is a mostly unseen link to the past. No markers indicate its existence and, for now, no plaques offer information about its history. The road that used to access Kinney Camp - a collection of historic corrals, barn, a 1-1/2-story house and other buildings - was closed in the 2000s after the ranch was vandalized. It’s just a short, worthwhile walk from Highway 140.

Kinney Camp is an historical ranch that’s part of the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge, just south of the Oregon-Nevada border. It was built more than 100 years ago by William K. Ebeling, a German immigrant who ran horses, cattle and sheep in the high desert of far northeastern California and Nevada from 1890 to 1917. Kinney Camp was one of Ebeling's three ranches.

Kinney Camp was used as a sub-ranch for workers on Ebeling’s sprawling holdings. The ranch name derives from a squatter named McKenney who had a small land claim near the mouth of Big Spring Gorge.

Kinney camp buildings, main house with new roof

The main house—with its 2-foot-thick walls, two bedrooms, kitchen, dining room, pantry, wood stoves and large upstairs room—was occupied on a year-round basis by a hired hand and, sometimes, his family. Duties included overseeing cows, sheep and a larger number of horses. During the ranch’s heydays, other ranch hands lived in the second story of a 12- by 14-foot bunkhouse atop an adjacent building that had a meat storage cellar.

Ebeling sold Kinney Camp and his other holdings to the Denio Land and Livestock Company in 1917, which later sold out to the Thousand Creek Land and Livestock Company before the property became part of the Sheldon in 1936.

| |

Ebeling sold Kinney Camp and his other holdings to the Denio Land and Livestock Company in 1917, which later sold out to the Thousand Creek Land and Livestock Company before the property became part of the Sheldon in 1936.

|

|

|

|

| |

Corrals made from willows |

|

Juniper posts hold willows |

|

Kinney Camp retains its history through its structures, including the house, combination meat storage/bunkhouse, root cellar, chicken house, barn and, possibly most fascinating, its corrals. Unique to ranches in the high desert are corrals made from juniper posts interlaced with willows. The signature horse barn is built from uncoursed pink sandstone block and basalt cobbled walls, with small rectangular windows framed with Dufurrena sandstone.

Windows framed by Dufurrena sandstone

Barn enclosed by willow fence

"These are unique ranch buildings," Lou Ann Speulda, a Fish and Wildlife Service historian and archaeologist, says of the barn and buildings. "It would be nice if we knew more about the lifestyle of the people who lived here and the ranching tradition. Intrinsically, they are part of our past and if we don't save them, then we don't have that connection," She wants to preserve Kinney Camp and other historic ranches because, "It makes it more real when you can walk out here and see the willow corrals. I think it's important that people understand how people lived. It's a totally different lifestyle from today. Ultimately, it'd be nice if we could restore this enough so that people could see what it was like."

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

View from the barn |

|

The roof that was |

|

Sheldon manager Brian Day said there are plans to place a plaque with a brief history of Kinney Camp at the undeveloped parking area located on the north side of Highway 140/Humboldt County Road 140, at milepost 95, 15 miles south of the Oregon-Nevada state line. It’s an easy 10- to 15-minute walk to the former ranch. Kinney Camp is a fascinating place. Its unusual structures recall hard-scrabble times, times when juniper stakes and willow branches were commonly used for corrals and pens because, unlike barbed wire, they were free and abundantly availabie. Kinney Camp remains as a place to speculate on the past, to listen to the winds yowl through its hollow structures.

Olene—A Place Most People, Not Knowing its Past, Drive Past

Olene is a place most people drive past. Located ten miles southeast of Klamath Falls along Highway 140, Olene is an unincorporated community and, for the most part, is considered "that is a town that was.'

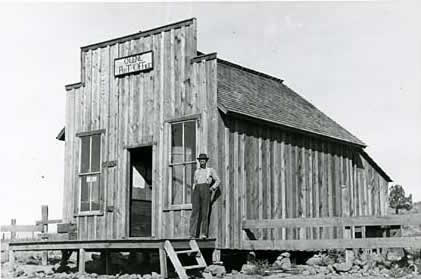

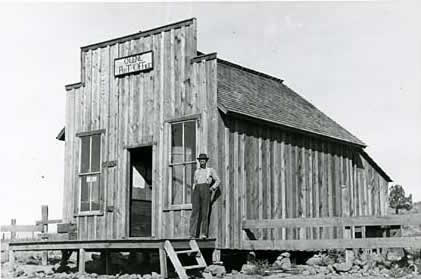

The old Post Office and general store in Olene (Klamath County Museum)

Olene is a place with a past. Its general store/gas station closed in the 2000s. A post office, originally located along the Lost River, opened in 1884 but was closed in 1966. During its heyday, Olene had a post office, two general stores, a hotel, blacksmith shop, a school, and a feed store. In 1940 Olene had 62 residents and was known as a prosperous dairy and potato farming community.

C'waam (sucker fish) drying on racks beside the Lost River (Klamath County Museum)

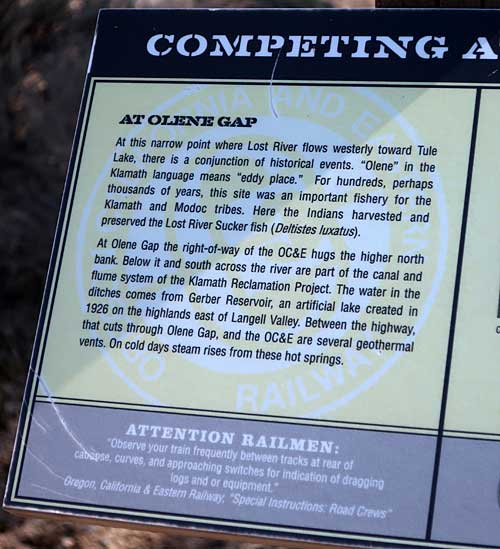

In much earlier years, Olene was a place where Klamath and Modoc Indians gathered seasonally to catch Lost River, or “C’waam,” sucker fish. According to Oregon Geographic Names, Olene gets its name from an Indian word meaning “eddy place,” or “place of drift.” That name was adopted by O.C. Applegate in 1884 when the first post office was established.

In Frontier Stories of the Klamath Country, historian Carrol Howe writes: “The hard rock river bottom here caused the suckers to come near the surface where they could be speared, snagged or netted. Old-time residents said the fish came in such hordes that a wagon could be filled using a pitchfork. Even after the diversion dam was built downriver from Olene, it became a popular place for the Indians to fish, socialize, and especially to gamble.”

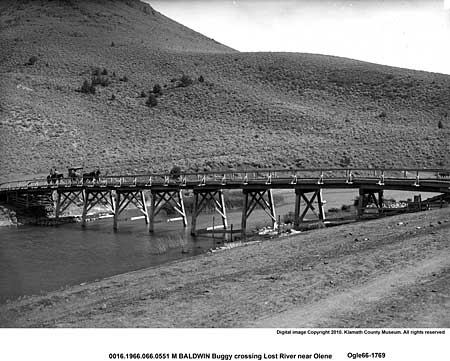

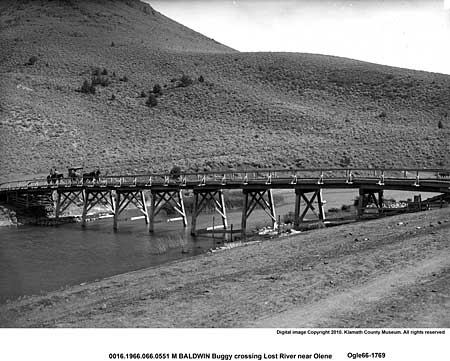

A buggy crosses the old bridge over the Lost River near Olene (Klamath County Museum)

A newer bridge across the Lost River (Klamath County Museum)

In later years, Olene was along the rail line built by the Oregon, California and Eastern Railway, or OC&E, a logging railroad that extended 64 miles from Klamath Falls past Olene to Bly. For many years the rail line was jointly operated by Southern Pacific and Burlington Northern and carried logs from the Bly area and logging camps along the Sycan River to mills in Klamath Falls. This line was bought by Weyerhaeuser in 1975, which also sent logs by rail to its Klamath Falls mill. After logging operations lessened, the right-of-way was railbanked in 1992 to the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, which converted it to the existing OC&E Woods Line State Trail.

One of the snowplows used to clear the railroad track is displayed at Olene

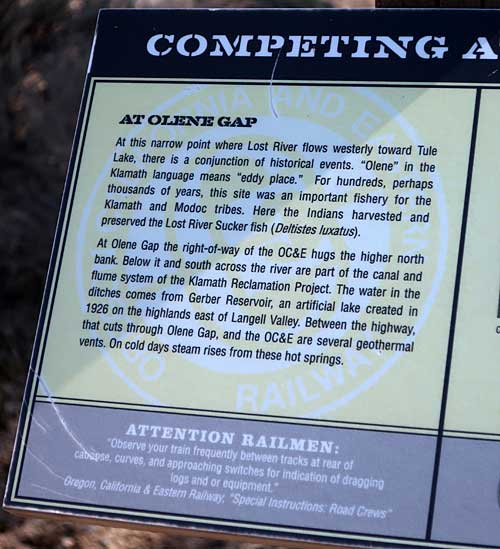

Sign on the OC&E trail describe Olene's history

Other memories of the railroad and the community’s history are preserved through interpretive signs along what is now the OC&E Woods Line State Trail.

Gerlach and Empire – They're Gonna Put Me in the Movies

When motorists driving along Washoe County Highway 447 reach Gerlach, Nevada, they’re welcomed by a sign that reads:

“Fastest Town in the West”

“Population: Wanted (sometimes)”

“Gerlach More Than Just a Pretty Name”

“Where the Pavement Ends & The West Begins"

“Potluck Capital of the World”

“5, 4, 3 Bars, No Churches, No Wars”

“Is It October Yet?”

An older sign, which was replaced because it was falling apart, also included such quips as, “That’s Why They Call It Girl Lack,” “The Time That Town Forgot,” and “Attitude Good.”

Welcome to Gerlach (Kristy Evans)

With a population that’s been fluctuating in recent years, from an estimated high of about 465 in the 1990s to about 100 in the early 2000s, and back up to 200–plus in 2021, Gerlach is a place remote from other cities. Located on the southern edge of the Black Rock and Smoke Creek deserts, it’s 100–plus-miles from Reno, Nevada, and about the same distance to Alturas, California. Townspeople used to boast that Gerlach had five bars and no churches. There are now three bars and still no church.

Seven miles south of Gerlach is Empire. For decades Gerlach’s economy largely depended on Empire, where United States Gypsum Corporation ran a gypsum mining operation. Empire came into being as a mining town when the mill was built in 1946. At its peak, Empire had a population of 465 with a combined total of about 800 in Empire and Gerlach. When the mine closed in 2011, leaving 95 people without jobs, Empire’s population seriously declined. The Empire Mining Company bought and reopened the gypsum mine in 2016 and refurbished some of the company town’s homes. Empire’s population has risen to an estimated 30 residents, but its zip code was eliminated after the mill closure. Gypsum was previously used to create sheet rock but it is now produced for agricultural uses.

Rugged Gerlach area landscape (Kristy Evans)

| |

|

|

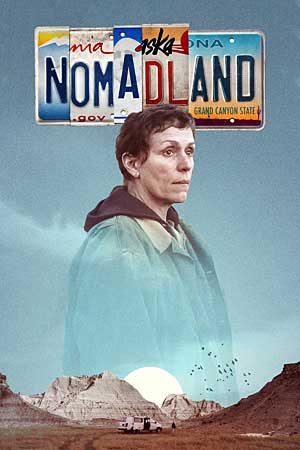

A portion of Nomadland, a movie starring Oscar-winner Frances McDormand, was filmed in Empire. The movie was named Best Film at the 2021 Golden Globes, was nominated for six 2021 Academy Awards, including Best Picture. It won Best Best Actress for McDormand, Best Director, and Best Picture. Some Empire residents had small roles and the film’s producers sponsored a showing in Empire after its release. The Empire mill was closed for a day for filming.

Nomadland and the mill’s reopening have injected new life into Gerlach and Empire. Most of Empire’s residents moved from their company-owned homes at the end of the 2011 school year, when Gerlach High School had nine graduating seniors. The school’s enrollment dropped from 80 students in 2011 to eight in 2012 but rebounded to 26 in 2021. The school, which has students in kindergarten through grade 12, also houses the city’s small library. |

|

| |

Award winning Nomadland |

|

|

|

Since the Burning Man event began in 1990, Empire and Gerlach have been tied to “Black Rock City,” an area on the nearby Black Rock Desert northeast of Gerlach that comes to life each Labor Day Weekend. Held on Bureau of Land Management land, the Burning Man gathering had more than 80,000 attendees In 2019. Known for its “anything goes” attitude, the festival always culminates with the burning of a giant specially-built figure of a man.

Bruno’s Country Club (Kristy Evans)

For decades Gerlach’s known person was the late Bruno Selmi, who owned Bruno’s Country Club, a popular restaurant and bar. Selmi retired from his businesses—including the restaurant, gas station, motel and trailer park—in 2012 after 61 years and died at age 94 in 2017.

Selmi is one of Gerlach’s most influential figures, but the area’s history dates back much earlier. In 1843, John C. Fremont, “The Pathfinder,” camped at Boiling Hot Springs, just north of the present-day town. Next came pioneer wagon trains traveling the Noble Road, a breakoff route from the better-known Applegate–Lassen Trail that curves just north of Gerlach through the Black Rock Desert.

Downtown Gerlach (Kristy Evans)

The Black Rock Desert was also the location of the “Thrust 2” project, when Britain’s Richard Nobel set the then-world land speed record of 633.468 miles per hour. Several movies have been filmed locally, including 1989’s Far From Home, starring Drew Barrymore, and, even earlier in 1926, Gary Cooper in The Winning of Barbara Worth.

Gerlach’s is named for Louis Gerlach, who began the Gerlach Land and Cattle Company in the early 1900s, but the town’s growth and beginnings date to 1905 when Western Pacific Railroad laid tracks for the Feather River Route from Winnemucca, Nevada. The railroad owned the town until 1972, when it sold lots that had previously been leased to townspeople.

Gerlach's Miners Club

Along with Bruno’s, businesses include the Black Rock Mud Company, which features “100 percent organic mineral-rich mud that finds its way to the earth through small bubbling mud volcanoes.” The town has a radio station, KLAP, 89.5-FM, The Miners Club, a coffee shop-bar, and Joe’s Gerlach Club which offers pool, slots, a jukebox and “fun … if the lights are on.” A non-profit organization, the "Friends of Black Rock High Rock," works with other partners to “maintain the health and well-being of the "Black Rock Desert/Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area” and arranges tours of Fly Geyser. Near Gerlach is Planet X Pottery, a pottery business that has operated since 1974 and is known for its fine porcelain, Raku and stoneware. In Empire is the Empire Store, “the only market in any direction for 80 miles.”

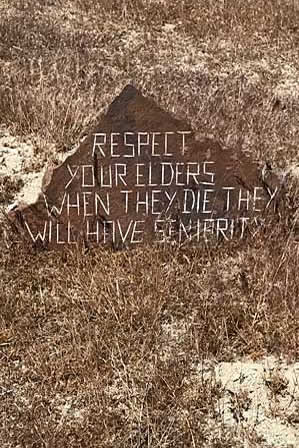

Guru Road is a landmark

Two miles north of Gerlach is Guru Road, also called Dooby Road, a mile-long dirt road created by DeWayne “Doobie” Williams. The road features stones engraved or painted with eclectic words of wisdom and advice, along with tributes to Williams’ family, friends, and area residents. Unusual items include a "weather station," a tribute to Elvis Presley, a marker honoring Aphrodite, a Trickle Down Art Show and a “Desert Broadcast System.”

The Welcome Sign is always up (Kristy Evans)

Gerlach and neighboring Empire may not be the "Center of the Universe" but these are places that might be dubbed, "Where the Present Is Past."

Notes

For information about the Shaw Historical Library and its annual journals, including Far Corners and Far Corners Two, visit the website at www.oit.edu/shaw/, email shawlib@oit.edu or call 541-885-1686. For information about Kinney Camp and the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge call 775-941-0199 or visit the Sheldon website at www.few.gov/refuge/Sheldon.

About the Author

Lee Juillerat is a semi-retired reporter-photographer who lives in Southern Oregon and is a frequent contributor to several magazines and other publications. He has written and co-authored books about various topics, most recently "Ranchers and Ranching: Cowboy Country Yesterday and Today.” Lee has produced photo-stories about U.S. and worldwide travels in High On Adventure for more than 20 years. He can be contacted at 337lee337@charter.net.

|

|